The Science Behind Why Adolescents Stay Up Late

Most high school students are familiar with the feeling of staying up late and then struggling to get up in the morning. Adolescents often prefer to go to bed late, but must wake up early in the morning for school when their bodies still need more rest, causing them to be sleep-deprived (Carskadon, 2011). While different adolescents need different amounts of sleep, the recommended range is eight to 10 hours. According to a 2021 survey by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 77% of high school students get less than this (CDC, 2024). On weekends, high school students wake up about 1.5 hours later than they do on school days, with the difference between weekday and weekend sleep schedules being greater every year of high school (Carskadon, 2011). However, the desire to sleep later is not just a result of too much screen time or too much homework; it is a biological shift that occurs for nearly all mammals during puberty. When one hits puberty, they experience shifts in the two main systems that regulate sleep: circadian rhythm and homeostatic drive. These shifts delay sleep and waking times (Hagenauer et al., 2009).

The Circadian Rhythm

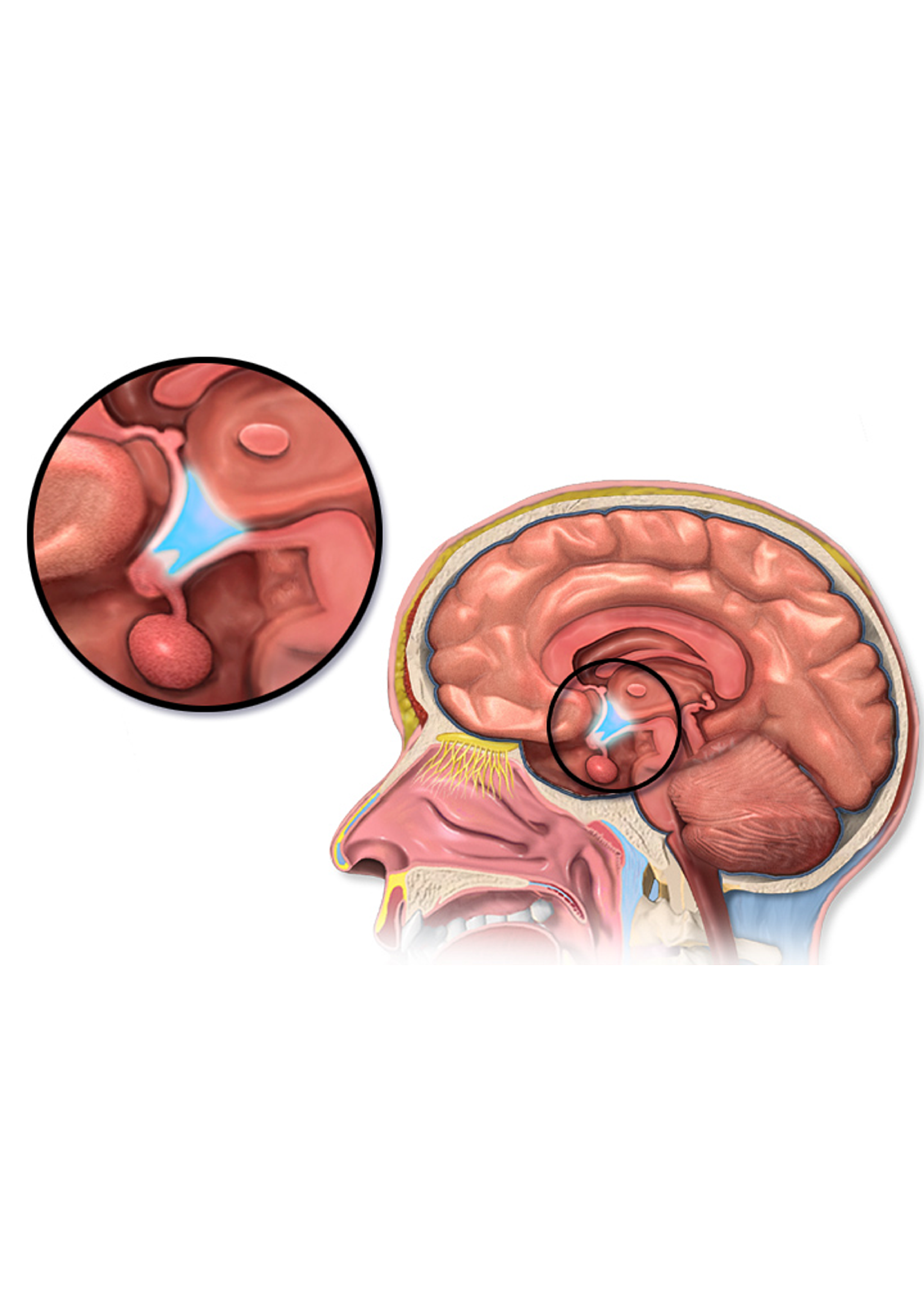

The circadian rhythm is the body’s 24-hour internal clock cycle that regulates the timing of sleepiness and alertness. It is controlled by the hypothalamus, a small region at the base of the brain that maintains homeostasis by regulating hormone release and controlling functions such as sleep, temperature, and hunger. During puberty, the hypothalamus goes through many changes, mainly caused by the release of sex hormones such as estrogen and testosterone (Hagenauer et al., 2009). A key change that happens to the circadian rhythm during puberty is that the release of melatonin, which signals to the body to go to sleep, occurs later in the evening. As a result, adolescents feel tired later than younger children and older adults. This shift is prevalent even under controlled lab conditions, where adolescents were exposed to light at the same time as patients of other ages in the study (Carskadon, 2011). On average, females tend to experience this delay a year before males because they hit puberty earlier (Hagenauer et al., 2009).

While studies disagree on the exact magnitude, they show that adolescents’ circadian rhythms are generally delayed by one to three hours compared to children and adults. This pattern is true for humans as well as many other mammals, such as monkeys and rats (Carskadon, 2011). This suggests that the shift to later sleep is driven by a biological change that occurs in adolescents.

However, one’s environment can make the delay even worse. Evening artificial light exposure from screens can trick the hypothalamus into thinking it is earlier than it actually is. Adolescents are more sensitive to exposure to light at night than adults are, further widening the gap between the sleep timing of adolescents and others. (Carskadon, 2011). An experiment with mice confirms this theory, showing that pubertal mice experienced more of a circadian rhythm delay than adult mice did when exposed to light in the evening (Hagenauer et al., 2009). All in all, the circadian rhythm of adolescents is naturally shifted later, and this shift is exacerbated by exposure to light in the evening.

Homeostatic Drive

The second system that helps regulate sleep, and is altered in adolescents, is the homeostatic drive, also known as “sleep pressure.” This means that the longer one is awake and the less sleep one has gotten, the more the brain pushes for sleep. During puberty, adolescents have an increased resistance to this sleep pressure, meaning they can stay awake for longer periods of time without feeling as tired. Scientists are not sure why this change occurs, though some speculate it is related to hormonal changes, physical growth, or a maturing brain (Carskadon, 2011).

Scientists can measure sleep pressure by looking at slow-wave activity in the brain. Slow wave activity is defined as brain waves within a certain frequency band. Adolescents who have hit puberty showed less slow-wave brain activity after being awake for a long period of time compared to people who have not yet hit puberty (Hagenauer et al., 2009). This means that if a adolescent has been awake for many hours, their brains do not “notice” this sleep deprivation as much as younger brains do. This delay of tiredness has been demonstrated and proved through scientific experiments in which participants were kept awake for long periods of time. In a study of nine to 14 year olds, some of whom had already hit puberty, the ones who were more mature were able to stay up for a longer period of time (Carskadon, 2011).

While the buildup of sleep pressure slows down in adolescents, the rate at which it dissipates during sleep remains the same. This means that while adolescents do not feel tired as quickly, they still need almost as much sleep as younger children because their brains recover at the same rate during sleep (Carskadon, 2011).

Conclusion

With nearly 80% of high school students not getting enough sleep, a frequent suggestion is to just “go to bed earlier,” but that is easier said than done. There are biological shifts that occur during puberty that make it difficult for adolescents to fall asleep early. During adolescence, the circadian rhythm shifts later, and sleep pressure builds more slowly. So, even if an adolescent wakes up early in the morning (for example, to go to school), they are less likely to feel especially tired that evening. These biological changes, combined with environmental factors, make it extremely difficult for adolescents to get the sleep they need. By understanding the science behind why adolescents stay up late, people can create strategies to help adolescents get the sleep they need, such as limiting evening screen time, keeping consistent sleep schedules, and advocating for later school start times.

References

Hagenauer, M.H., Perryman, J.I., Lee, T.M., & Carskadon, M.A. (2009). Adolescent Changes in the Homeostatic and Circadian Regulation of Sleep. Developmental Neuroscience, 31(4). https://doi.org/10.1159/000216538

Carskadon, Mary A. (2011). Sleep in adolescents: the perfect storm. Pediatric clinics of North America, 58(3), 637–647. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcl.2011.03.003

FastStats: Sleep in High School Students. (2024, May 15). U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved October 5, 2025, from https://www.cdc.gov/sleep/data-research/facts-stats/high-school-students-sleep-facts-and-stats.html

Blaus, B. (2014, February 11). Hypothalamus location [Photograph]. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Blausen_0536_HypothalamusLocation.png